BJS Academy>Surgical science>The microbiome and s...

The microbiome and surgery: breakthrough or just hype?

John C. Alverdy MD FACS FSIS1, Benjamin Shogan MD2

1Sarah and Harold Lincoln Thompson Professor Executive Vice Chair

Chicago, Illinois, @JCAlvery, jalverdy@surgery.bsd.uchicago.edu

2Department of Surgery, University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine, bshogan@surgery.bsd.uchicago.edu

Related articles

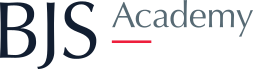

Review of: Contribution of the patient microbiome to surgical site infection and antibiotic prophylaxis failure in spine surgery

F.F. van den Berg1, M.A. Boermeester2

1Department of Medical Microbiology, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

2Department of Surgery, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Article review Long, D. R. et al. Contribution of the patient microbiome to surgical site infection and antibiotic prophylaxis failure in spine surgery. Sci. Transl. Med.16, eadk8222 (2024). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.adk8222

Personalized neoadjuvant immunotherapy for stage III malignant melanoma: notes on the PRADO study

1Aikaterini Dedeilia, M.D, 2Genevieve Boland, MD, PhD

1Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Surgical Oncology Research Laboratories; Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital; Research Fellow in Surgery, Harvard Medical School.

2Vice Chair of Research, Department of Surgery; Section Head, Melanoma/Sarcoma Surgery; Surgical Director, Termeer Center for Targeted Therapies; Director, Surgical Oncology Research Laboratories, Massachusetts General Hospital; Associate Professor of Surgery, Harvard Medical School.

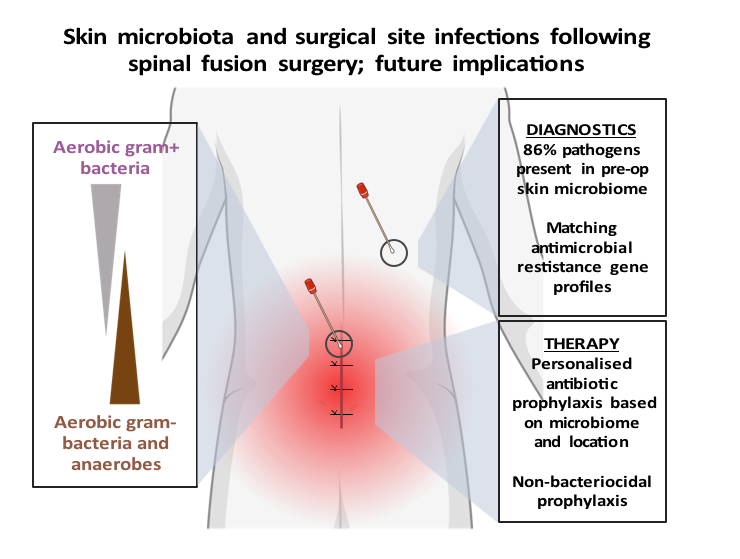

Background While significant changes have occurred in the management of microscopic stage III disease due to the data from MSLT-21, the current standard of care for macroscopic stage III nodal malignant melanoma consists of initial surgical treatment with therapeutic lymph node dissection (TLND), followed by consideration for adjuvant therapy consisting of either anti-PD-1 monotherapy2 or BRAF/MEK inhibitors3. This results in improved relapse-free survival, but recurrence is still observed in almost half of the patients within 3-5 years4-6. Preclinical trials7-9 and emerging clinical data10 suggest that neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibition may have clinical benefit over adjuvant approaches. Given increasing enthusiasm for adjuvant and neoadjuvant approaches, the OpACIN (NCT02437279, phase I) and OpACIN-neo (NCT02977052, phase II) studies were established to investigate the safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) combination, and to establish optimal dosing regimens to maximize clinical benefit while minimizing toxicity in patients with stage III melanoma. The OpACIN and OpACIN-neo trials

Discussion of: decellularized adipose matrices can alleviate radiation-induced skin fibrosis; adv wound care (New Rochelle).

Kanad Ghosh, MD1; Hannes Prescher, MD1; Summer E. Hanson, MD, PhD, FACS1

1Section of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Chicago Medicine and Biological Sciences, Chicago, IL, 60637

With the advent of cellular targets and immunotherapy, cancer treatment has undergone significant improvement over the past several decades. While curative treatment of malignancy often relies on surgical excision, adjuvant modalities such as loco-regional irradiation remain important tools in comprehensive cancer care. Adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) is highly effective in reducing cancer burden, limiting the need for extensive surgery and decreasing the risk of local recurrence.1-3 However, RT brings collateral damage to the healthy surrounding soft tissues. Exposure to ionizing radiation results in a series of tissue changes marked by erythema, ulceration and oedema in the acute phase, followed by chronic inflammation and skin fibrosis, which may persist after treatment 4,5. As cancer survival rates continue to improve, an increasing number of patients are living with chronic morbidity related to RT. Autologous fat transfer (AFT) has emerged as a possible treatment to the harmful effects of irradiation.6,7 Here, adipose tissue is suctioned from one part of the body, processed and then injected in small aliquots directly into the irradiated tissues.8 The mechanism through which lipoaspirate exerts a reparative effect is poorly understood but thought to be through direct and indirect actions: direct differentiation of transferred adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) into new adipocytes, and paracrine signalling of cytokines and growth factors (HGF, TGF-ß, FGF-1,2, VEGF) that inhibit profibrotic signalling pathways and contribute to the recruitment of proangiogenic cells 9. Like a skin graft, the adipose graft in AFT is dependent on the recipient tissue bed for nutrition and engraftment to achieve adequate ‘take.’ One of the challenges of fat grafting, in particular into a poorly perfused, irradiated tissue bed, is its unreliable retention rate, which is cited at between 30%-70%. Repeat procedures are often performed.10,11 As an alternative to AFT, decellularized adipose matrices (DAM) derived from discarded lipoaspirate have been developed. The allografts are processed through physical, chemical, and enzymatic purification techniques to develop decellularized scaffolds that retain the complex macromolecular architecture of the adipose tissue, and potentially its paracrine function via key growth factors retained in the graft. In recent studies, DAMs have been shown to promote adipose tissue regeneration, and have become a promising alternative to traditional fat grafting for soft tissue defects. 12 However, DAMs have not been studied in the context of radiation or a former tumour bed.

Copied!