BJS Academy>Continuing surgical ...>Widening participati...

Widening participation in cardiothoracic healthcare: INSINC Insight

Kirstie Kirkley

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; United Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust

Georgia R. Layton

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust

Javeria Tariq

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Heen Shamaz

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; University of Edinburgh

Mostin Hu

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; University of Cambridge

Alana Atkinson

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; Queen’s University, Belfast

Deborah Harrington

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Elizabeth Belcher

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; Oxford University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Jason Ali

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; Royal Papworth NHS Trust

Narain Moorjani

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; Royal Papworth NHS Trust

Farah Bhatti

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; Swansea Bay University Healthboard

Karen Booth

Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland; Newcastle Upon Tyne NHS Foundation Trust

Related articles

ERAS – yesterday, today and also for tomorrow? The ERAS Society perspective.

Olle Ljungqvist, Ulf Gustafsson, Hans D. de Boer

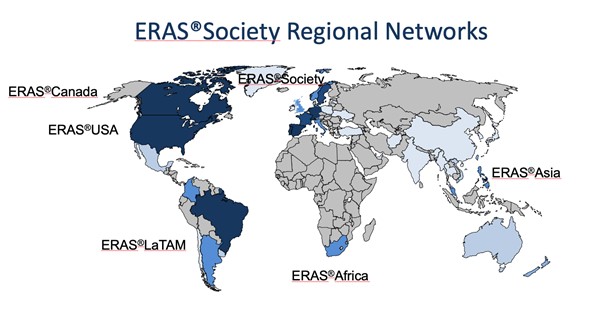

ERAS so far It is more than 25 years ago that a multimodal approach to recovery after major surgery, called fast track surgery, was first proposed1,2. Combined with laparoscopic surgery it showed that old and frail patients were fit to leave the hospital in two days after major surgery3. Larger follow up studies reported that this could be achieved with fast track surgery alone. This inspired a group of surgeons from Northern Europe to form the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Study Group in 20014. The members hypothesized that bringing together all potential stress reducing and recovery improving care elements into one program, would enhance recovery after surgery. The first ERAS protocol was published in 20055. But alongside the guideline there was a need to also organize care in a new way to make ERAS fully functioning6 (Table 1). When the guideline was tested a clear relationship was shown with more care elements in the protocol in use and improved outcomes regarding both complications, length of stay and readmissions suggesting that detailed audit would be key7-9.

Robotics surgery

Omar Yusef Kudsi, MD, MBA, FACS

Introduction With multiple advantages over laparoscopic and open surgery, including stereovision, enhanced precision and dexterity, surgeons are transitioning to robotic surgery. Practicing robotic surgeons praise the platform’s improved ergonomics and camera control, advantages that are worth the challenge of overcoming the steep learning curve. Thus, robotics is becoming the cornerstone for advancing the field of minimally invasive surgery. An obvious pattern in the diffusion of cutting-edge technologies is that it starts with one manufacturer – Intuitive Surgical has currently near complete dominance of the robotic surgery market. However, in the future, new robotic platforms will become available. Here we discuss the advantages and challenges with robotic surgery.

Resilience and the modern surgeon

Dr Agnes Arnold-Forster

Military metaphors The place (and some of the problem) of resilience in surgery lies in its origins in the profession’s long historical association with the military. In the nineteenth century, members of the medical professions exploited and elaborated, as historian Michael Brown has put it, “visions of masculinity framed by war, heroism, and self-sacrifice.”1 Clinical practice was conceptualised as a form of warfare against a malevolent enemy and military metaphors were used to refer both to the activities of germs, gangrene, and cancerous tumours, and to the actions of surgeons and physicians. The military metaphor worked on multiple levels. Surgeons were waging war against damage, disability, and disease – inanimate, if deadly foes. Surgeons were also increasingly seen as part of a society-wide conflict between life and death, cures and killers, progress and stagnation. In 1900, Surgeon-Extraordinary to Queen Victoria, Frederick Treves, spoke at the annual meeting of the British Medical Association. His address entitled, ‘The surgeon in the nineteenth century,’ concluded with a flourish, reflecting on the future of surgeon in a passage suffused with military language: “So as one great surgeon after another drops out of the ranks, his place is rapidly and imperceptibly filled, and the advancing line goes on with still the same solid and unbroken front.”2

Copied!