BJS Academy>Continuing surgical ...>Robotics surgery

Surgical digest

Robotics surgery

Omar Yusef Kudsi, MD, MBA, FACS

Chair, Department of Surgery Director, Robotic Surgery Fellowship Department of Surgery, Good Samaritan Medical Center Associate Professor, Tufts University School of Medicine Massachussets, USAOmar.kudsi@tufts.edu

Related articles

ERAS – yesterday, today and also for tomorrow? The ERAS Society perspective.

Olle Ljungqvist, Ulf Gustafsson, Hans D. de Boer

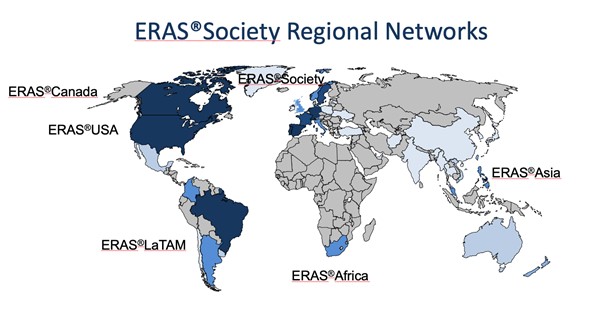

ERAS so far It is more than 25 years ago that a multimodal approach to recovery after major surgery, called fast track surgery, was first proposed1,2. Combined with laparoscopic surgery it showed that old and frail patients were fit to leave the hospital in two days after major surgery3. Larger follow up studies reported that this could be achieved with fast track surgery alone. This inspired a group of surgeons from Northern Europe to form the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Study Group in 20014. The members hypothesized that bringing together all potential stress reducing and recovery improving care elements into one program, would enhance recovery after surgery. The first ERAS protocol was published in 20055. But alongside the guideline there was a need to also organize care in a new way to make ERAS fully functioning6 (Table 1). When the guideline was tested a clear relationship was shown with more care elements in the protocol in use and improved outcomes regarding both complications, length of stay and readmissions suggesting that detailed audit would be key7-9.

Resilience and the modern surgeon

Dr Agnes Arnold-Forster

Military metaphors The place (and some of the problem) of resilience in surgery lies in its origins in the profession’s long historical association with the military. In the nineteenth century, members of the medical professions exploited and elaborated, as historian Michael Brown has put it, “visions of masculinity framed by war, heroism, and self-sacrifice.”1 Clinical practice was conceptualised as a form of warfare against a malevolent enemy and military metaphors were used to refer both to the activities of germs, gangrene, and cancerous tumours, and to the actions of surgeons and physicians. The military metaphor worked on multiple levels. Surgeons were waging war against damage, disability, and disease – inanimate, if deadly foes. Surgeons were also increasingly seen as part of a society-wide conflict between life and death, cures and killers, progress and stagnation. In 1900, Surgeon-Extraordinary to Queen Victoria, Frederick Treves, spoke at the annual meeting of the British Medical Association. His address entitled, ‘The surgeon in the nineteenth century,’ concluded with a flourish, reflecting on the future of surgeon in a passage suffused with military language: “So as one great surgeon after another drops out of the ranks, his place is rapidly and imperceptibly filled, and the advancing line goes on with still the same solid and unbroken front.”2

Is there a role for coaching in surgical training and beyond?

Rebecca Winterborn

I have often wondered why as Consultant Surgeons we do not have coaches. Professional sportspeople, singers and even high-end executives receive coaching throughout their careers. Why is it that we think as surgeons we magically become competent and stay competent? Why do we still follow a model of pedagogy, where there is a presumption that, following a period of teaching, after a certain point, instruction is no longer needed. ‘You’re cooked’ and you can go the rest of the way yourself, with a reliance on continuing personal development. Back in 2011, Atul Gawande authored an article in The New Yorker entitled Personal Best1. He noted that within 10 years of completing his surgical training he had reached a plateau. His rate of complications steadily lowered to better than average and there they stayed. It felt to him like the only direction they could go, was backwards. He reflected that his outcomes were not necessarily about his evolving practical skills but more about familiarity and judgment. Would coaching help to maintain his outcomes, in the same way that coaching helps to maintain Rafa Nadal’s outcomes playing tennis. He enlisted the support of a retired colleague who observed him in theatre and offered advice and coaching. He noted that his complication rates started to reduce again as he applied the insights.

Copied!

Connect

Copyright © 2026 River Valley Technologies Limited. All rights reserved.

.png)

.jpg)