BJS Academy>Cutting edge blog>Guest post: Mental h...

Guest post: Mental health and BRCA

Grace Brough, Douglas Macmillan, Kristjan Asgeirsson, and Emma Wilson Division of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Nottingham Nottingham Breast Institute, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust

27 November 2020

Guest Blog Breast

Related articles

Guest blog: Invasive lobular cancer of the breast remains a surgical challenge

U Narbe, P -O Bendahl, M Fernö, C Ingvar, L Dihge, L Rydén

Invasive lobular breast cancer is the second most common histological subtype and constitutes around 10-15% of all breast cancer. It is recognized by a peculiar diffuse growth pattern and disseminated spread of cancer cells contributing to diagnostic delay and difficulties in detecting the primary tumors by mammography and nodal metastasis by axillary ultrasound. Consequently, although invasive lobular breast cancer mainly displays a favorable luminal A molecular subtype, it is often diagnosed at a higher stage than invasive cancer of no special type. Despite these characteristics, histopathological subtype is not accounted for in Clinical Guidelines, in contrast to the molecular subtypes. In the BJS publication “The St. Gallen 2019 Guidelines understage the Axilla in Lobular Breast Cancer: a Population-Based Study” by Ulrik Narbe and co-authors, we have elaborated on the consequences for patients with invasive lobular cancers if completion axillary clearance would be omitted in patients with 1-2 nodal metastases.

For the breast surgeon, lobular cancer poses a challenge to surgery of the breast and to the axilla. Large tumor size and diffuse infiltrating margins are associated with an increased risk of positive margins after breast conserving surgery and in breast centers where MRI is available, complementary imaging is recommended ahead of primary surgery. Still a larger proportion of patients (66%) with lobular cancer undergo a mastectomy compared to other histological subtypes (43%) according to our registry study, supporting previous publications. So the dogma of de-escalating breast surgery from mastectomy to partial mastectomy in lobular cancer is challenging, keeping in mind that positive resection margins is a mandatory quality criteria in most centers pushing the choice of initial surgery towards upfront mastectomy.

Axillary surgery is moving towards de-escalation of surgical interventions for patients with 1-2 sentinel node metastases after the results of the Z0011 trial have been implemented worldwide and clearly supports that omission of completion axillary dissection is non-inferior provided the inclusion criteria for the trial is fulfilled. The Z0011 criteria for omission of completion axillary dissection is restricted to patients undergoing breast-conserving surgery, and is thus not applicable for lobular cancers operated by mastectomy. The St. Gallen 2019 guidelines extended the indication for abstaining completion axillary dissection to all patients of any tumor size irrespective of type of breast surgery. In addition, the guidelines recommended that the decision on adjuvant chemotherapy for luminal A-like tumors should include nodal staging and patients with 4 or more nodal metastasis (nodal stage II) were recommended adjuvant chemotherapy. For these patients there is hitherto no data on the role of genomic tests for risk stratification until the results of OPTIMA trial are presented. In this paper, we present data from the National Swedish Quality Registry with prospectively collected data retrieved from the period when a completion axillary clearance for patients with sentinel node metastases was recommended. We found a strong association between invasive lobular breast cancer and nodal stage II disease independent of other determinants such as tumour size.

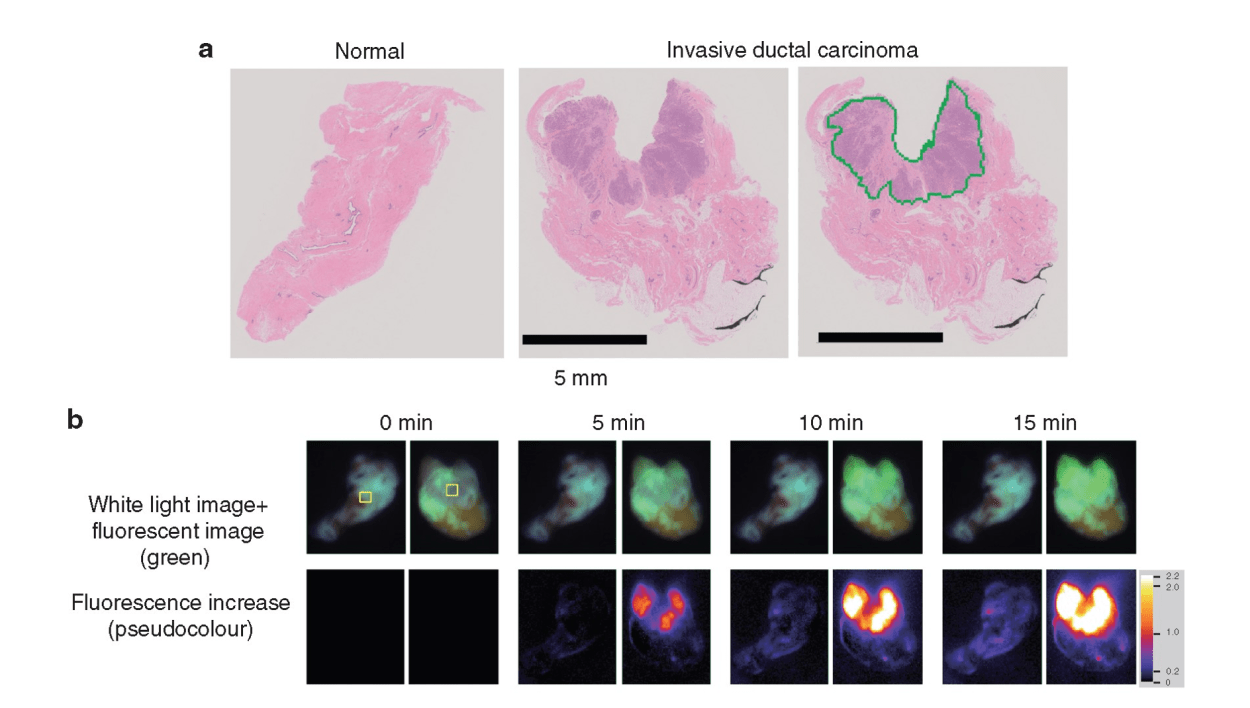

Guest blog: a novel fluorescence technique for detecting breast cancer

Hiroki Ueo, Department of Surgery and Sciences, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan; Ueo Breast Cancer Hospital, Oita, Japan

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, and its incidence continues to increase worldwide. From the patient’s perspective, breast conserving surgery (BCS) with radiation achieves a balance between a satisfactory cosmetic result and a low recurrence rate. Although it has been established as a routine surgery, surgeons need to be careful about positive surgical margins. Remnant cancer cells in the preserved tissue increase the risk of recurrence. Therefore, a positive margin on postoperative pathology warrants additional surgery. In these cases, the additional treatment harbours unexpected outcomes, including physical, mental, cosmetic, and economic burden on the patients.

To avoid the additional operation, pathological evaluation using an intraoperative frozen section is conducted. It is the most reliable method to prevent misdiagnosis and to achieve clear surgical margins. However, this conventional method is time consuming and costly. Moreover, it is dependent on the skill and experience of the pathologists and personnel, and it requires space for preparation of the frozen sections. Therefore, only a limited number of samples are examined to save time and resources. An alternative, rapid, and reliable technique to detect cancer in surgical margins enables simultaneous testing, leading to a reduced false negative rate of local recurrence incidence. In addition, pathologists can focus on the definitive diagnosis using permanent paraffin sections because it is difficult to make a diagnosis based on intraoperative frozen sections without pathological architecture. Pathologists only need to make an intraoperative diagnosis when the specimen cannot be evaluated via the fluorescence procedure. Thus, it is important to enhance the rapid fluorescent detection of breast cancer during surgery. To address these diagnostic issues, Prof. Urano invented chemical reagents (gamma-glutamyl hydroxymethyl rhodamine green [gGlu-HMRG]) that quickly fluoresce by reacting with an enzyme (gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT]), overexpressed in cancerous tissues. It exhibits strong fluorescence a few minutes after reacting with GGT in vitro. A gGlu-HMRG solution is applied to the surgical margins to recognize cancer cells as green fluorescence intraoperatively. A previous study in 2015 documented the ability of this reagent to mark cancerous tissues in surgical breast tissues. Furthermore, this reagent did not interfere with the pathological examination, while the frozen section analysis tissues were difficult to reuse as formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded permanent pathological specimens.

The clinical utility of this technique was examined. The results were published in the British Journal of Surgery. Since the initial report in 2015, a more feasible and reproducible sample preparation protocol has been developed. Then, a dedicated apparatus, including a built-in camera, software programme, and multiple sample wells, was developed. This system automatically measured and analyzed the increase in fluorescence of multiple samples simultaneously. Then, the increase in fluorescence of gGlu-HMRG, applied to breast tissues, was measured in four different institutes. The sample tissues were examined by four pathologists independently. These pathologists diagnosed the samples without knowing the background information of the patients. The clinical utility of the current fluorescent procedure was evaluated by comparing the fluorescence data and the pathological diagnosis.

The iBRA-NET Localisation Study: A national prospective cohort study comparing the safety and effectiveness of wire- and magnetic seed-guided localisation for non-palpable breast lesions.

Rajiv V Dave, Emma Barrett, Jenna Morgan, Mihir Chandarana, Suzanne Elgammal, Nicola Barnes, Amtul Sami, Tahir Masudi, Sue Down, Chris Holcombe, Shelley Potter, Santosh K. Somasundaram, Matthew Gardiner, Senthurun Mylvaganam, Anthony Maxwell, James Harvey, iBRA-NET Localisation Study collaborative.

In recent years there has been an increasing focus on the evaluation of medical devices. Approval of medical devices for clinical use is approached in a different way from medicines; they require a demonstration of safety when implanted, but require little in the way of prospective evidence for their efficacy. Once a device is approved by a regulatory authority it can be used by clinicians without mandate for further research or audit on the product. This has inevitably led to manufacturers marketing their products to clinicians, often with little or no published evidence as to their efficacy. Historically, the introduction of devices following regulatory approval has taken a path many of us would have witnessed; a few early adopters work with the manufacturer to develop a small series, often in multiple centres, in a disjointed manner. Hence, over time a novel device may be supported by several small case series, performed in potentially biased sites. These series are often reported with inconsistent outcome measures and differing methodology. The majority of these studies would not have a control group for comparison, making it difficult to establish the true benefits or harms of this novel device.

This approach has inherent drawbacks for both manufacturers, and for surgeons and patients. Manufacturers may often support a series of small studies at moderate cost, which can be slow to deliver and/or be published. The data generated are often not directly comparable or able to be analysed collectively. With regards to patients; Is it right to place a device for which you have no outcome data? Is it right to place a device without consenting that you are new to using this device, with little known about its outcomes? Lastly, why would surgeons use a novel device with little evidence base? There are clearly a multitude of reasons; the device may be an improvement from established practice, there may be pressure from manufacturers, and they may be driven by the desire to be the first to use a device, along with the potential kudos for publishing or presenting on the subject.

The iBRA-NET was established to find a better way of evaluating devices new to the market. As a collaborative group we wished to establish a framework for research and audit of outcomes of new devices, with a robust governance structure. There was an imperative need to study localisation devices for impalpable breast cancers, due to their rapid introduction into the clinical setting, and the relatively short-term follow-up requirements meant that this was a deliverable study. The manuscript sets out how we established a prospective national study to evaluate all new breast localisation devices, comparing these to the historical standard of wire localisation. The simple aims of the study were to provide patients, clinicians and manufacturers with robustly-audited outcomes for these localisation devices, and to provide a platform for shared learning on device usage, with oversight of this evaluation from a body of professionals committed to the safe introduction of surgical devices.

Copied!

Connect

Copyright © 2026 River Valley Technologies Limited. All rights reserved.

.png)

.jpg)