BJS Academy>Cutting edge blog>Guest post: To contr...

Guest post: To control or be controlled by the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19)?

Johannes Kurt Schultz is a surgeon at the Akershus university Hospital in Norway.

26 March 2020

Guest Blog General

Related articles

Invited Commentary: Associations between adverse outcomes for surgical admissions and nurse understaffing – a longitudinal study

Petter Frühling, MD, PhD,1 and Patricia Tejedor, MD, PhD2

1. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Unit, Department of Surgery, Department of Surgical Sciences, Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden.

2. University Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Colorectal Surgery Unit, Madrid, Spain

In a recent study published in BJS, Meredith1 and co-authors present their findings of the detrimental effects of nurse understaffing and adverse events for surgical patients. This, as the authors highlight, is a critical yet often overlooked problem that extends far beyond the National Health Service (NHS) in England. Although the paper’s conclusion that ‘understaffing’ is ‘associated with increased risks of a range of adverse events’ may appear obvious, the significance of the findings relies on its universal character – that it is a global problem that requires urgent attention.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has de facto identified a global shortage of healthcare workers, particularly nurses and midwives, who represent more than 50% of the current shortfall. While the shortage of doctors may be manageable, the understaffing of nurses poses a severe threat to health outcomes. In a large observational study, that included nine European countries and data from more than 420 000 patients, published in Lancet in 2014, it was noted that each increase of one patient per nurse was associated with a 7% increase in the likelihood of a surgical patient dying within 30 days of admission2.

Two recent reports from the International Council of Nurses (ICN) further emphasise the detrimental effects of nurse understaffing on patient outcomes, and urge readers to view this as a matter of global urgency. In Sustain and Retain in 2022 and Beyond3 the authors project the need to replace up to 13 million nurses globally in the coming years, reflecting alarming rates of nurse attrition driven by stress, burnout, absenteeism, and industrial action. The ICN’s 2023 follow-up report, Recover to Rebuild – Investing in the Nursing Workforce for Health System Effectiveness , calls for a coordinated global effort to establish a sustainable nursing workforce through a long-term, ten-year plan.

Surgical research in Plain English

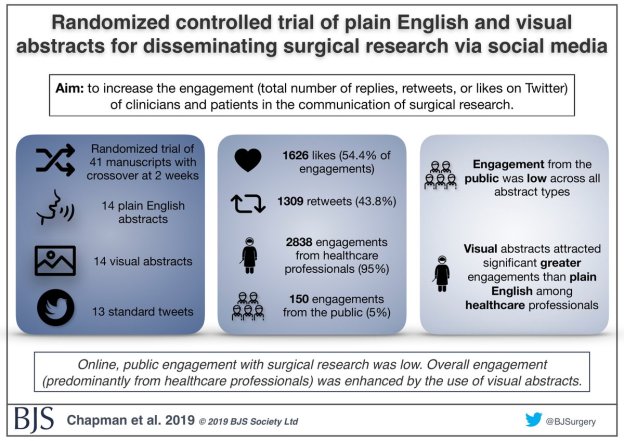

Randomized controlled trial of plain English and visual abstracts for disseminating surgical research via social media

BJS started with the aim of of being a medium through which surgeons “can make our voice intelligibly heard”, according to Sir Rickman Godlee, President of the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1913.

The aim of a recently published paper in BJS was to increase the engagement (defined compositely as the total number of replies, retweets, or likes on Twitter) of clinicians and patients in the communication of surgical research – part of the core values of BJS.

Guest post: The effects of COVID-19 on surgeons and patients

Gianluca Pellino (@GianlucaPellino) and Antonino Spinelli (@AntoninoSpin) are surgeons from Italy.

When the first cases of the disease that would have been later named COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) caused by SARS-CoV2 were described in Wuhan approximately three months ago, it would have been difficult to predict the impact and the burden that the subsequent outbreak would have had globally. The first case was tracked back to November 2019, indeed the spread COVID-19 proved to be incredibly rapid, and is currently causing several challenges to most health systems.

On the 11th March the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 pandemic. Between the last week of February and the first week of March, the number of cases outside China increased 13-fold and the numbers of affected countries tripled. By the time the present piece is being typed, 164 837 cases were recorded globally, with 6470 deaths, 146 countries involved.

Among European countries, Italy has been hit first and more deeply, the reasons for this still being analysed, and no agreed explanation available. Since the first cases were described on the 30th January 2020, two Chinese tourists, the outbreak showed a logarithmic growth, and by today (16/03/2020), the overall number of individuals who tested positive was 24 747 (20 603 still positive) with 1809 deaths. This would mean a mortality rate overall as high as 7.3%, and 43.6% of those who had an outcome. Of those currently infected, approximately 8% is in serious/critical conditions. Lombardy, considered the economic heart of Italy, where an ideal health system is in place, registered the highest number of COVID-19, exceeding 13 200 patients, more than half than all Italian cases. The outbreak is rapidly spreading to the entire peninsula, islands not being spared: almost 1000 cases between South and Islands (3.73%). Even if these figures might not seem worrisome, they actually are, as facilities and infrastructures might not be prepared to afford a similar outbreak as that observed in Northern Italy, and the system could collapse. Restrictive measures had to be taken, and the Italian Government ordered an unpreceded lockdown effective as the 12th March 2020, and its effect and meaning are well testified by the empty Italian cities. Florence’s Uffizi Gallery is closed; St. Peter’s Square in Rome is empty.

Copied!

Connect

Copyright © 2026 River Valley Technologies Limited. All rights reserved.

.jpg)