BJS Academy>Cutting edge blog>Guest blog in plain ...

Guest blog in plain English: Hernias in children

Nathalie Auger, Francesca del Giorgio, Annie Le-Nguyen, Marianne Bilodeau-Bertrand, Nelson Piché University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

3 December 2021

Guest Blog Hernia

Related articles

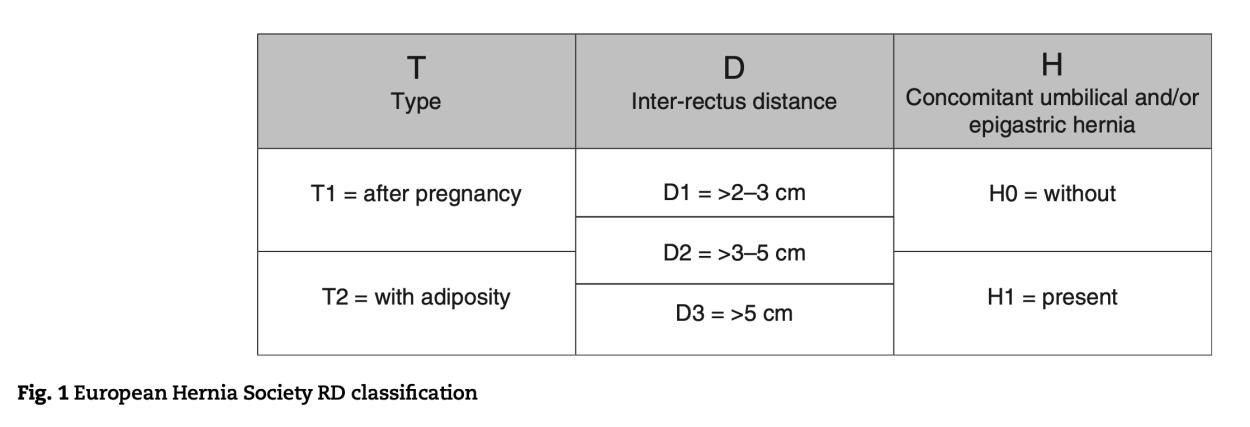

European Hernia Society guidelines on management of rectus diastasis

Eight surgeons came together to review the available evidence on the management of rectus diastasis and produce evidence-based guidelines. Sadly the evidence quality ranged from very low to moderate. Despite this, the team were able to provide nine recommendations, with the strength of the recommendation ranging from weak to strong.

The nine key questions were:

KQ1 What is the definition of RD?

Parastomal hernia: Quality of life

Imran Mohamed, Rhiannon L Harries

The recent article1 outlined the techniques used in contemporary management of parastomal hernia. Reported outcomes are centred around surgical site complications and recurrence. There is, however, a huge burden placed upon the patient who ultimately has to manage the physical as well as psychological stresses associated with a parastomal hernia. There is growing interest in developing optimal management strategies that take into account patient reported outcomes, that do not simply focus on clinical determinants such as successful operative repair.

Patients with parastomal hernia have worse physical functioning, experience more pain and have lower general health as well as experiencing feelings of negative body image, compared to patients without parastomal hernia2,3. Body image encompasses perceptions, emotions and attitudes a person holds with regards to their own body3. Interventions can be designed to improve perceptions of body image, as well as levels of physical activity.

The Hernia Active Living Trial (HALT) aims to evaluate the effect of increased physical activity on the risk of parastomal hernia development3. Increased levels of physical activity may contribute towards improving overall perceptions of body image and also quality of life.

PelvEx 2024

John T. Jenkins1, Paul Sutton2

1. Consultant Colorectal Surgeon

Chair of Surgery

Lead Complex & Recurrent Cancer Service,

St. Mark's Hospital, London

Imperial College, London

Surgeon to the Royal Household

2. Consultant Colorectal, Pelvic, and Peritoneal Surgeon

Colorectal and Peritoneal Oncology Centre

The Christie NHS Foundation Trust

Chair ACPGBI Advanced Malignancy Subcommittee

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58974/bjss/azbc052

PelvEx 2024 was hosted and organized in London by the ACPGBI Advanced Malignancy Subcommittee and UKPEN. The Royal Institution provided the perfect venue, blending history with excellent facilities which ensured the meeting was a tremendous success. Nearly 300 delegates attended from all over the world, with this year’s meeting having a truly multi-disciplinary programme.

The first day included sessions on “R0 resection – How important is it really”, “How much is too much in exenteration surgery”, and “Mastering morbidity”. In addition, sessions on the “Consequences of exenteration surgery” including patient and nursing experiences, as well as discussion about sex and intimacy, and the psychological consequences of surgery. The day finished with a “Consultants Corner- Grey Heads on Green Shoulders” session discussing a number of diverse challenges encountered at different stages in clinical practice .

The second day began with the inaugural trainee prize presentation session for the now coveted Brunschwig Prize. A number of high quality abstracts were received and the six best (linked below this blog) were invited to deliver oral presentations. The quality was exceptional. This session was followed by sessions on “Research progress” and “Surgical techniques”, followed by an afternoon where the “Oncologists have their say” culminating with a “Global MDT”. The conference was live streamed to China and recorded for posterity.

Copied!

Connect

Copyright © 2026 River Valley Technologies Limited. All rights reserved.

.jpg)