BJS Academy>Cutting edge blog>Author response: Lon...

Author response: Long-term risk prediction after major lower limb amputation: 1-year results of the PERCEIVE study

Brenig Llwyd Gwilym1, Philip Pallmann2, Cherry-Ann Waldron2, Lucy Brookes-Howell2, Emma Thomas-Jones2, Christopher Twine3, Adrian Edwards2,4, David Charles Bosanquet1 on behalf of the PERCEIVE study group

1. South East Wales Vascular Network, Cardiff, UK

2. Centre for Trials Research, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK

3. Bristol Centre for Surgical Research, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

4. Division of Population Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK

Correspondence to: Brenig Llwyd Gwilym (email: brenig.gwilym@wales.nhs.uk)

Ward B2

University Hospital of Wales

Heath

Cardiff CF14 4XW

UK

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58974/bjss/azbc058

Related articles

Comment on: Long-term risk prediction after major lower limb amputation: 1-year results of the PERCEIVE study

Daniel C. Norvell1,2,3, Alison W. Henderson1,3 and Joseph M. Czerniecki1,2,3

1. VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, Washington, USA

2. Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA

3. VA Center for Limb Loss and Mobility (CLiMB), Seattle, Washington, USA

Correspondence to: Daniel C. Norvell (email: Daniel.norvell@va.gov)

1660 S. Columbian Way

Seattle

Washington 98108

USA

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development Grants number (O1474-R) and (1 I01 RX002960-01).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58974/bjss/azbc054

Dear Editor

We would like to commend Gwilym and colleagues for their commitment to amputation level shared decision-making. The PERCEIVE trial was a major undertaking requiring a large collaboration1.

Plain English Summary: How the first COVID‐19 wave affected UK vascular services

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted healthcare around the world. Patients who have vascular disease (problems with their arteries or veins), are at high-risk of having complications if they develop COVID-19. This is because patients with vascular disease usually have many medical problems. Some of them are also elderly and might be frail. We do not know how the COVID-19 pandemic might have affected the care of patients with vascular disease.

The COVER study is an international study trying to assess how the COVID-19 pandemic changed the medical care of patients with vascular disease. The first part of the COVER study was an internet survey. In this survey, doctors and healthcare professionals were asked questions (every week) about the care of vascular patients at their hospital. The results were published in this article.

The results showed that the COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on vascular services worldwide. Most of the 249 hospitals taking part from 53 countries, reported big reductions in numbers of operations performed and the types of services they could offer to patients with vascular disease. Almost half of the hospitals stopped doing routine scans to detect artery problems and a third had to stop all clinics in the height of the pandemic. There were major changes in the resources available to treat blocked leg arteries. Most non-urgent operations, especially for vein problems, were cancelled.

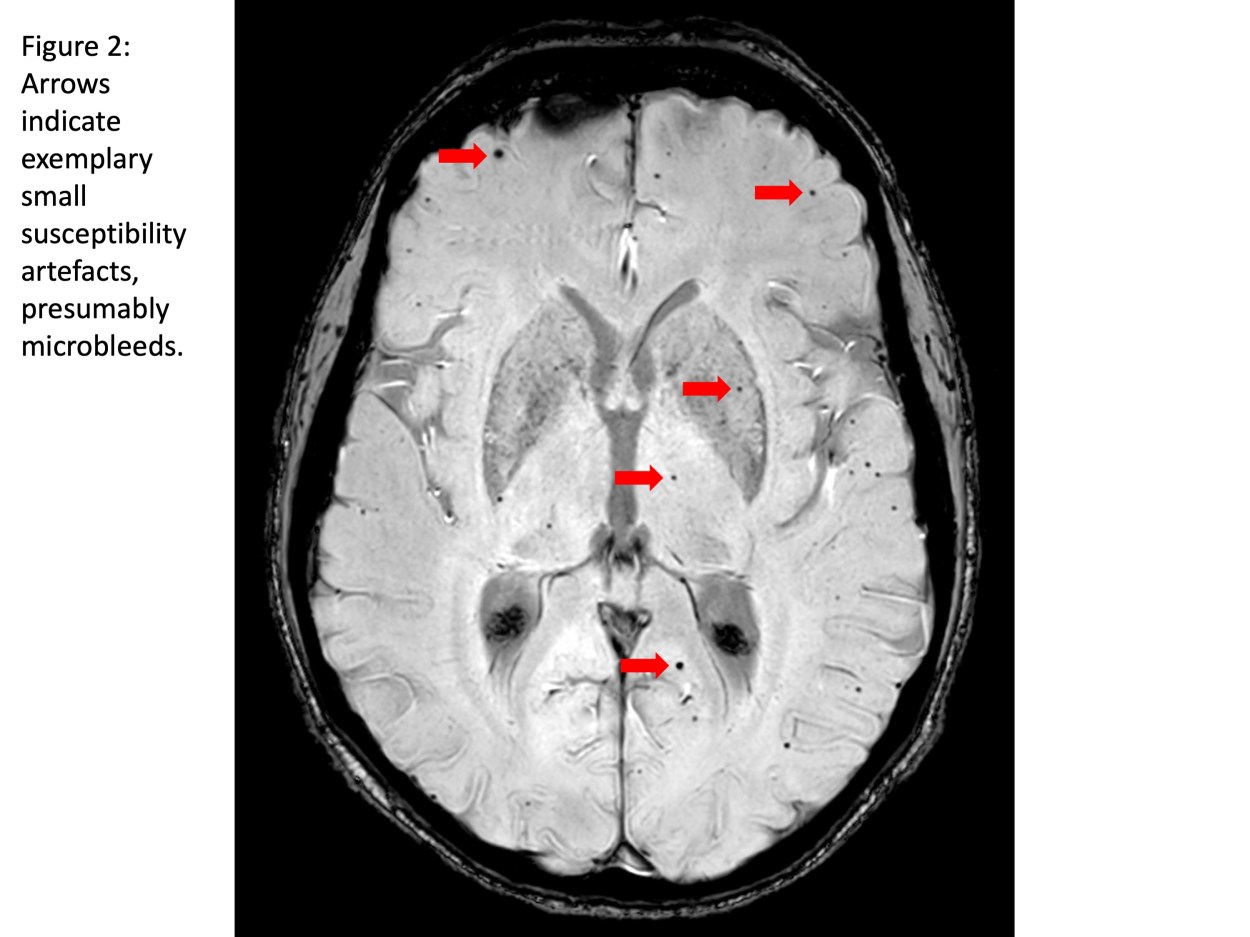

Guest blog: Cerebral microbleeds following thoracic endovascular aortic repair

W. Eilenberg a,b**, M. Bechstein d**, P. Charbonneauc, F. Rohlffs a, A. Eleshra a, G. Panuccio a, J. Bhangu b, J. Fiehler d, R. Greenhalgh e, S. Haulon c, T. Kölbel a*

a German Aortic Center, Department of Vascular Medicine, University Heart & Vascular Center, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

b Department of General Surgery, Division of Vascular Surgery, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

c Centre de l’Aorte, Hôpital Marie Lannelongue, Groupe hospitalier Paris Saint Joseph, Université Paris Saclay, France

d Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

e Vascular Surgical Research Group, Imperial College, London, UK.

** both authors contributed equally

E-mail:

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Stroke and cerebral damage are frequent findings after thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) with a postoperative clinical stroke rate of 3-4% and silent brain infarcts (SBI) in about 80%.(1-4) However, the mechanism of stroke and subclinical cerebral damage in TEVAR is under-investigated. Current clinical research-efforts such as the STEP-registry (strokes from thoracic endovascular procedures) aim to better understand incidence of, and risk factors for stroke and cerebral damage after TEVAR, and to develop strategies for prevention.(5, 6) More than 60% of patients undergoing arch-TEVAR were reported to have SBIs on diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) despite protective efforts such as carbon dioxide (CO2) flushing of the endografts.(5, 6) The aim of the current study is to examine the occurrence of CMBs in patients after TEVAR within the STEP-registry and to evaluate their association with patient- and procedural factors.

Ninety-one patients treated with TEVAR in proximal landing zone (PLZ) 0-3 from September 2018 to January 2020 at the German Aortic Center (Hamburg, Germany) and Marie Lannelongue Hospital (Paris, France) were included in the study.(5) The location and number of CMBs were identified and analyzed with regards to procedural aspects, clinical outcome and Fazekas-score as indicator of preexisting vascular leukoencephalopathy.

Copied!

Connect

Copyright © 2025 River Valley Technologies Limited. All rights reserved.

.jpg)